The Netherlands, or Holland, is rather a small country but we have a lot of medieval history. Really, we are greater than we are small! And this has been my goal ever since I re-joined the SCA in 2011: to teach you about my country’s fabulous history.

Allow me to take you to the north of my country, a province called Friesland.

The Frisii were among the migrating Germanic tribes that, following the breakup of Celtic Europe in the 4th century BC, settled along the North Sea. They came to control the area from roughly present-day Bremen to Bruges, and conquered many of the smaller offshore islands. What little is known of the Frisii is provided by a few Roman accounts, most of them military. Pliny the Elder said “their lands were forest-covered with tall trees growing up to the edge of the lakes.” They lived by agricultureand raising cattle.

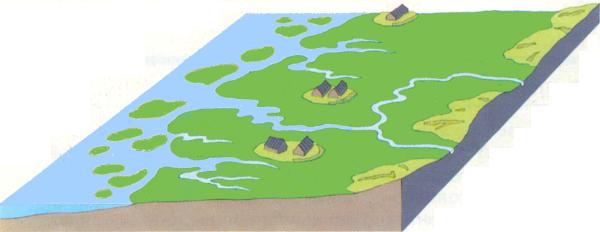

The constant battle against the tides made it necessary to create high hills to build houses on, to raise cattle and to grow crops and provide safe ground during high tide and river floods. These mounds are artificial dwelling hills created for habitation, as early as 600 BC.

The mounds, or TERPEN as we call them, were up to 15 metres (49 ft) high to be safe from the floods in periods of rising sea levels. The first terp building period dates from 500 BC, the second from 200 BC to 50 BC. In the mid-3rd century, the rise of sea level was so dramatic that the north Frisian clay district was deserted, and settlers returned around AD 400. A third terp building period dates from AD 700. This ended with the coming of the dike somewhere around 1200. There used to be 955 mounds in Friesland, now there are only a few left. The Aalsum mound produced interesting items during extensive archaeological research some 30 years ago.

During the excavations the mounds proved to be rich with interesting rubbish and personal waste deposited by their inhabitants during centuries, a true feast for archaeologists. The Aalsum hat was excavated in 1979. The textile itself wasn’t easily dated, but carbon dating on household items found right next to the hat indicated the items to be from 700-900 AD.

Although there was a lot of trade between the Terp inhabitants and the surrounding areas (we know this from coins from Scandinavia and Germany found during the excavation), most of the clothes and fabric for normal everyday use were made at home on the, for that time, familiar standing weaving loom.

These excavated textiles contain information not only about how a fabric was spun, dyed and woven. They also give information about finishing processes and about how a fabric was put together, sewn, used and repaired.

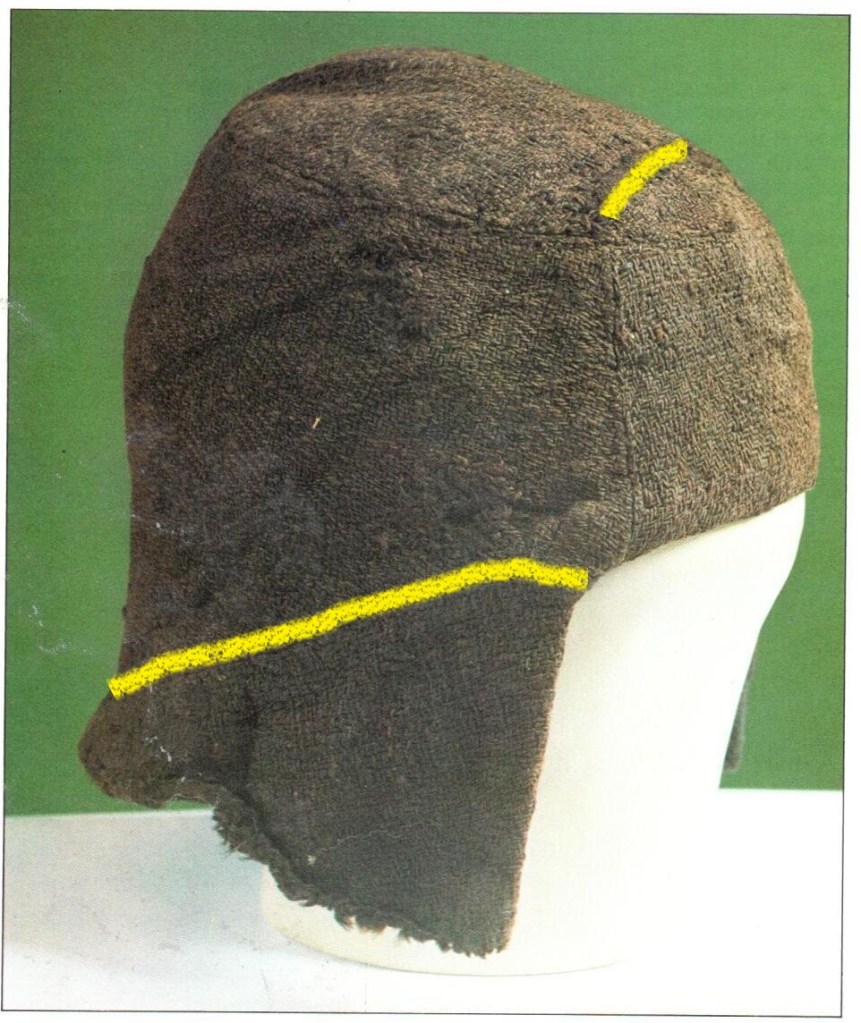

The Aalsum hat was made of different types of wool or tweed. The yarn was untwined and for the weft a single strand was used in all pieces of fabric. It appears to have been a hat made of fabric “leftovers”. While carefully analysing the hat, the Frisian museum’s curator found that it was made of five pieces of fabric. For this reproduction we decided to make the hat of just of three pieces, because this made no difference in the final result and style of the hat.

The yellow lines show the crown part consisted of two pieces and the right side flap also had two pieces. These two parts of the pattern were left out in the ‘new’ version. The round top part of the pattern was sewn to the rest of the hat with the braid stitch (see further down). The other pattern pieces were sewn together with a back stitch and decorated with a blanket stitch around the face and around the neck. Interestingly enough, there are two ways of wearing the Aalsum hat, making it incredibly hard to define as a hat for a man, or for a woman? And, now that we are on that topic, does that really matter? I say NO! We can all wear this hat!

Though the Aalsum hat was made of left overs, it was quite carefully sewn, with the use of fine sewing threads and small stitches. In my opinion, this was no simple hat made for one season. The decorative braid stitch on the original hat is a complicated braid stitch of which you will find the picture here. The stitch is time consuming, but very well worth it!

Although this braid stitch lies on top of the fabric and can look a bit rough, it is rather subtle needlework. This stitch allows the fabric to stay flat and still sew the hat together, creating a seam that is not bulky; the braid was decorative as well as functional. The hat is comfortable to wear this way! The use of decorative stitching is self-evidently more than simply functional. Probably the hat was valued for its colour, decoration and craftsmanship as well.

Here you see my own replica of this hat, my husband being the reluctant model. I used dark brown left over tweed and an old flanel shirt for the lining. Recycling baby! It’s better for the planet 😉

Textiles remnants, though difficult to date, still tell us a lot about the people who wore them. The area and time only add to the story and for us SCAdians those are wealthy resources. I chose this hat because of its versatility, after all, there are two ways of wearing it! It shows the flexibility of the craftsmen in those early days of my countries history: they knew how to make a lot out of limited resources. The 8th and 9th century were not the Dark Ages! They are filled with history and knowledge, and so were most of the people.

You can download the pattern here:

I would like to thank archeologist Chrystel Brandenburgh for helping me out with this!